Introduction

Probability Space

Probability space is a triple $(\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \mathbf{P})$ , comprised of the following three

elements:

1 Sample space $\Omega$ : the set of all possible outcomes of an experiment

2 $\sigma$ -algebra (or $\sigma$ -field) $\mathcal F$ : a collection of subsets of $\Omega$

3 Probability measure $\mathbf P$ : a function that assigns a nonnegative

probability to every set in the $\sigma$ -algebra $\mathcal F$

Sample space

Mutually exclusive: no identical element.

Collectively exhaustive: all results should be included.

$\sigma$ -algegra

not unique

3 requirements:

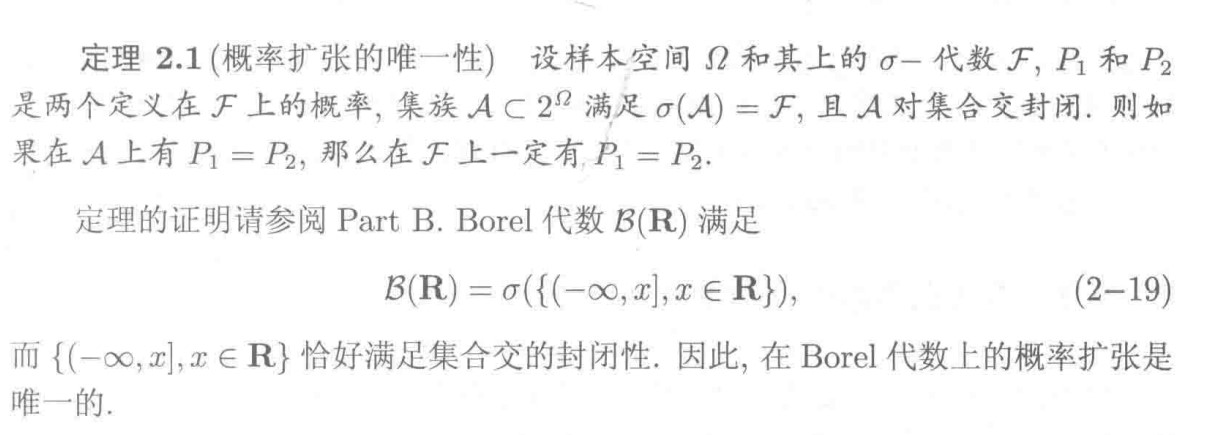

$$ \varnothing \in \mathcal F\\ \forall A \in \mathcal F, A^c \in \mathcal F\\ \forall A_k \in \mathcal F, k=1, 2, ..., \cup_{k=1}^{\infty}A_k\in \mathcal F $$Borel field

used to measure intervals

when $\Omega$ is continuous( $\R$ for example), Borel field is useful.

“minimum” $\sigma$ -algebra means deleting any element in the $\mathcal B (\mathbf R)$ will miss the requirements.

Uncountable

decimal numbers between 0 and 1 are uncountable.

Probability measures

$$ P:\mathcal F \rightarrow [0, 1] $$Nonnegativity $P(A)\ge0, \forall A \in \mathcal{ F}$

Normalization $P(\empty)=0, P(\Omega)=1$

Countable additivity $A_1, A_2, ... \text { is disjoint in }\mathcal F, P(A_1\cup A_2\cup ...)=P(A_1)+P(A_2)+...$

- They are the axioms of probability.

- Probability is a mapping from $\sigma$ -algebra to a real number betwenn 0 and 1, which intuitively specifies the “likelihood” of any event.

- There exist non-measurable sets, on which we cannot define a probability measure.

Discrete models

$$ P(\{s_1, ..., s_n\})=P(s_1)+...+P(s_n)\\ P(A) = \frac{\text{\# of elements of }A}{\text{total \# of elements of sample points}} $$Continuous Models

Probability = Area

Some properties of Probability measure

$$ A\sub B\Rightarrow P(A)\le P(B)\\ P(A\cup B)=P(A)+P(B)-P(A\cap B)\\ P(A\cup B) \le P(A) + P(B)\\ P(A\cup B \cup C)=P(A) + P(A^C\cap B) + P(A^C\cap B^C\cap C) $$Conditional Probability

$$ P(A|B)=\frac{P(A\cap B)}{P(B)} $$- If $P(B)=0$ , $P(A|B)$ is undefined.

- For a fixed event $B$ , $P(A|B)$ can be verified as a legitimate probability measure on the new universe. $P(A, B)\ge 0$ , $P(\Omega|B)=1$ , $P(A_1\cup A_2\cup...|B)=P(A_1|B)+P(A_2|B)+...$

- $P(A|B)=\frac{\text{ \# of elements of }A\cap B}{\text{total \# of elements of }B}$

Total probability theorem

Let $A_1, ..., A_n$ be disjoint events that form a partition of the sample space and assume that $P(A_i)>0$ for all $i$ . Then for any event B, we have

$$ P(B) = \sum_{i=1}^n P(A_i\cap B) = \sum_{i=1}^nP(A_i)P(B|A_i) $$Remark

- The definition of partition is that $\cup_{i=1}^n A_i = \Omega, A_i\cap A_j = \emptyset, \forall i\ne j$

- The probability of B is a weighted average of its conditional probability under each scenario

- Each scenario is weighted according to its prior probability

- Useful when $P(B|A_i)$ is known or easy to derive

Inference and Bayes’ rule

Let $A_1, ..., A_2$ be disjoint events that from a partition of the sample space and assume that $P(A_i) \gt 0$ for all $i$ . Then for any event $B$ such that $P(B)\gt 0$ , we have

$$ P(A_i|B) = \frac{P(A_i)P(B|A_i)}{P(B)} = \frac{P(A_i)P(B|A_i)}{\sum_{j=1}^nP(A_j)P(B|A_j)} $$Remarks

- Relates conditional probabilities of the form $P(A_i|B)$ with conditional probabilities of the form $P(B|A_i)$

- often used in inference: effect $B$ $\lrarr$ cause $A_i$

The meaning of $P(A_i|B)$ in the view of Bayes: the belief of $A_i$ is revised if we observed effect $B$ . If the cause and the effect are closely binded( $P(B|A_i) > P(B|A_i^c)$ ), then the belief $A_i$ is enhanced by the observation of effect $B$ ( $P(A_i|B) > P(A)$ ). This can be derived from the Bayes’ rule through simple calculation. If $P(A_i|B)=P(A_i)$ , then $B$ provides no information on $A_i$ .

Independence

Independence of two disjoint events

Events A and B are called independent if

$$ P(A\cap B) = P(A)\cdot P(B) $$or equivalently, when $P(B) > 0$ ,

$$ P(A|B) = P(A) $$Remarks

- Occurrence of B provides no information about A’s occurrence

- Equivalence due to $P(A\cap B) = P(B)\cdot P(A|B)$

- Symmetric with respect to $A$ and $B$ .

- applies even if $P(B) = 0$

- implies $P(B|A) = P(B)$ and $P(A|B^c) = P(A)$

- Does not imply that A and B are disjoint, indeed opposite!

- Two disjoint events are never independent!( $P(A\cap B) = 0$ , but $P(A)\cdot P(B)\ne 0$ )

Conditional independence

$$ P(A\cap B | C) = P(A| C) \cdot P(B|C) $$Definition

Event $A_1, A_2, ..., A_n$ are called independent if:

$$ P(A_i\cap A_j\cap ...\cap A_q) = P(A_1)P(A_j)...P(A_q) $$for any distinct indices $i, j, \dots q$ chosen from $\{1, \dots n\}$ .

Pairwise is independence does not imply independence.

Discrete Random Variables

Random Variable is neither random, nor variable.

Definition

We care about the probability that $X \le x$ instead $X = x$ in the consideration of generality.

Random variables

Given a probability space $(\Omega, F, P)$ , a random variable is a function $X: \Omega \rightarrow \R$ with the probability that $\{\omega \in \Omega: X(\omega) \le x\} \in \mathcal F$ for each $x\in \R$ . Such a function $X$ is said to be $\mathcal F$ -measurable.

Probability Mass Function(PMF)

$$ p_X(x)=P(X=x)=P(\{\omega \in \Omega \text{ s.t. } X(\omega)=x\}) $$Bonulli PMF:

$$ p_X(k) = \begin{cases} p, &\text{if } k = 1\\ 1-p, &\text{if }k=0 \end{cases} $$Binomial PMF: $p_X(k)=\binom{n}{k}p^k(1-p)^{n-k}$

Geometric PMF: $p_X(k)=(1-p)^{k-1}p$

Poisson PMF: $p_X(k)=e^{-\lambda}\frac{\lambda^k}{k!}$ . Note: $\sum_{k=0}^\infty e^{-\lambda}\frac{\lambda^k}{k!}=e^{-\lambda}e^\lambda=1$

If $y=g(x)$ , $p_Y(y)=\sum_{\lbrace x|g(x)=y \rbrace} p(x)$ .

Expectation and Variance

Expectation

$$ E[X] = \sum_x xp_X(x) $$Note: we assume that the sum converges.

Properties:

$$ E[Y]=\sum_x g(x)p_X(x)\\ E[\alpha X + \beta] = \alpha E[X] + \beta $$Variance

$$ \text{var}(X) = E \left[(X-E[X])^2\right]=\sum_x (x-E[X])^2 p_X(x) $$Standard deviation: $\sigma_X=\sqrt{\text{var}(X)}$

Properties:

$$ \text{var}(X) = E[X^2] -(E[X])^2\\ \text{var}(X)\ge 0\\ \text{var}(\alpha X + \beta) = \alpha^2\text{var} (X) $$Bernoulli RV

$$ p_X(k) = \begin{cases} p, &\text{if } k = 1\\ 1-p, &\text{if }k=0 \end{cases}\\ E[X] = p\\ E[X^2] = p\\ \text{var}(X) = p(1-p) $$Discrete Uniform RV

$$ p_X(k) = \begin{cases} \frac {1}{b-a+1}, &\text{if } k = a, a+1, ..., b\\ 0, &\text{otherwise} \end{cases}\\ E[X] = \frac{a+b}{2}\\ \text{var}(X) = \frac{(b-a)(b-a+2)}{12} $$Poisson RV

$$ p_X(k)=e^{-\lambda}\frac{\lambda^k}{k!}\\ E[X] = \lambda\\ \text{var}(X)=\lambda $$Conditional

$$ p_{X|A(x)} = P(X=x|A) = \frac{P(\{X=x\}\cap A)}{P(A)} $$ $$ \sum_x p_{X|A}(x) = 1 $$ $$ E[X|Y=y] = \sum_x xp_{X|Y}(x|y)\\ E[g(X)|Y=y] = \sum_x g(x)p_{X|Y}(x|y) $$Total expectation theorem

$A_1, \dots, A_n$ is a partition of sample space $$ P(B) = P(A_1)P(B|A_1) + \dotsb + P(A_n)P(B|A_n)\\ p_X(x) = P(A_1)p_{X|A_1}(x) + \dotsb + P(A_n)p_{X|A_n}(x)\\ E[X] = P(A_1)E[X|A_1] + \dotsb + P(A_n)E[X|A_n] $$We derive the expectation and variance use the theories above.

Geometric PMF example

$$ p_X(k) = (1-p)^{k-1}p, k = 1, 2, \dots\\ E[X] = \sum_{k=1}^\infty kp_X(k) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty k(1-p)^{k-1}p\\ E[X^2] = \sum_{k=1}^\infty k^2p_X(k) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty k^2(1-p)^{k-1}p\\ \text {var}(X) = E[X^2] - (E[X])^2 $$However, the Geometric has a memoryless property.

$$ p_{X|X>1}(k) = \frac{P(\{X>1\}\cap \{X=k\})}{P(X>1)} = \frac{(1-p)^{k-1}p}{1-p} = (1-p)^{k-2}p $$Thus,

$$ E[X] = P(X=1)E[X|X=1] + P(X>1)E[X|X>1]=p+(1-p)(E[1 + X])\\ \Rightarrow E[X] = 1/p\\ E[X^2] = P(X=1)E[X^2|X=1] + P(X>1)E[X^2|X>1] = p + (1-p)E[(1+X)^2]=p + (1-p)(1+2E[X]+E[X^2])\\ \Rightarrow E[X^2] = \frac{2-p}{p^2}\\ \Rightarrow\text{var} (X) = \frac{1-p}{p^2} $$Multiple discrete random variables

Joint PMFs

$$ p_{X, Y}(x, y) = P(X = x, Y= y) = P(\{X(\omega) = x\}\cap \{Y(\omega) = y\}) $$ $$ \sum_x\sum_y p_{X, Y}(x, y) = 1 $$Marginal PMF

$$ p_X(x) = \sum_y P(X=x, Y=y) = \sum_y p_{X, Y}(x, y) $$Conditional PMF

$$ p_{X|Y}(x|y) = P(X = x | Y = y) = \frac{p_{X, Y}(x, y)}{p_Y(y)} $$ $$ \sum_x p_{X|Y}(x|y) = 1 $$Funcitons of multiple RVs

$$ Z = g(X, Y)\\ p_Z(z) = \sum_{\lbrace (x, y)|g(x, y)=z \rbrace } p_{X, Y}(x, y) $$Expectations

$$ E[g(X, Y)] = \sum_x\sum_y g(x, y)p(X, Y)(x, y)\\ E[g(X, Y, Z)] = \sum_x\sum_y\sum_z g(x, y, z)p(X, Y, Z)(x, y, z) $$ $$ E[g(X, Y)] \not\equiv g(E[X], E[Y]) $$linearity

$$ E[\alpha X + \beta] = \alpha E[X] + \beta\\ E[X + Y + Z] = E[X] + E[Y] + E[Z] $$Let’s calculate the Mean of Binominal RV.

$$ X_i= \begin{cases} 1, &\text{if success in trial } i,\\ 0, & \text{otherwise.} \end{cases}\\ X = X_1 + X_2 + \dotsb X_n\\ E[X] = \sum_{i = 1}^n E[X_i] = np\\ \text{var}(X) = np(1-p) $$Independence

Independence

$$ p_{X, Y}(x, y) = p_X(x) \cdot p_Y(y) $$if $X$ and $Y$ are independent:

$$ E[XY] = E[X]E[Y]\\ E[g(X)h(Y)] = E[g(X)]E[h(Y)]\\ \text{var}(X + Y) = \text{var}(X) + \text{var}(Y) $$Conditional independence

$$ p_{X, Y|A}(X, Y) = p_{X|A}(x) \cdot p_{Y|A}(y) $$Continuous Random Variables

Probability Density Function

- $f_X(x)\ge 0\text{ for all }x$

- $\int_{-\infty}^\infty f_X(x)\mathrm dx = 1$

- If $\delta$ is very small, then $P([x, x+\delta])\approx f_X(x) \cdot \delta$

- For any subset $B$ of the real line, $P(X\in B) = \int_B f_X(x)\mathrm d x$ .

Expectation

$$ E[X] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty xf_X(x)\mathrm dx\\ E[g(x)] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty g(x)f_X(x)\mathrm dx $$Assuming that the integration is well-defined. The Cauchy distribution ( $\frac{1}{1+x^2}$ )doesn’t have expectation since $\frac{x}{1+x^2}$ is not absolutely integrably.

Variance

$$ \text{var}(X) = E[(X - E[X])^2] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty(x - E[x])^2 f_X(x)\mathrm dx\\ 0\le \text{var}(x) = E[X^2] - (E[X])^2 $$Uniform RV

$$ f_X(x) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{b-a}, &\text{if }a\le x\le b,\\ 0, &\text{otherwise.} \end{cases} $$ $$ E[X] = \frac{a+b}{2}\\ E[X^2] = \frac{a^2+b^2 + ab}{3}\\ \text{var}(X) = \frac{(b-a)^2}{12} $$Properties:

$$ E[aX+b] = aE[X] + b\\ \text{var}(aX+b) = a^2\text{var}(X) $$Common Example for PDF

Exponential Random Variable

$$ f_X(x) = \begin{cases} \lambda e^{-\lambda x}, &\text{if }x \ge 0,\\ 0, &\text{otherwise.} \end{cases} $$ $$ P(X\ge a) = e^{-\lambda a}\\ E[X] = \frac{1}{\lambda}\\ \text{var}(X) = \frac{1}{\lambda^2} $$Cumulative Distribution Functions

$$ F_X(x) = P(X\le x) = \begin{cases} \sum_{k\le x}p_X(k), &\text{if } X \text{ is discrete,}\\ \int_{-\infty}^x f_X(t)\mathrm dt, &\text{if } X \text{ is continuous.} \end{cases} $$Properties

$$ \text{if } x \le y, \text{then } F_X(x)\le F_X(y).\\ F_X(x)\text{ tends to 0 as } x \rightarrow -\infty, \text{and to 1 as} x \rightarrow \infty\\ \text{If } X \text{ is discrete, then } F_X(x) \text{ is a piecewise constant function of }x.\\ \text{If } X \text{ is continuous, then } F_X(x) \text{is a continuous funciton of }x.\\ \text{If } X \text{ is discrete and takes integer values, the PMF and the CDF can be obtained from each other by summing or differcing: }\\ F_X(k) = \sum_{i = -\infty}^k p_X(i),\\ p_X(k) = P(X\le k) - P(X \le k -1) = F_X(k) - F_X(k - 1),\\ \text{ for all integers }k.\\ \text{If } X \text{ is continuous, the PDF and the CDF can be obtained from each other by integration or differentiation: }\\ F_X(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_X(t)\mathrm dt, f_X(x) = \frac{\mathrm dF_X}{\mathrm dx}(x) $$Examples for CDF

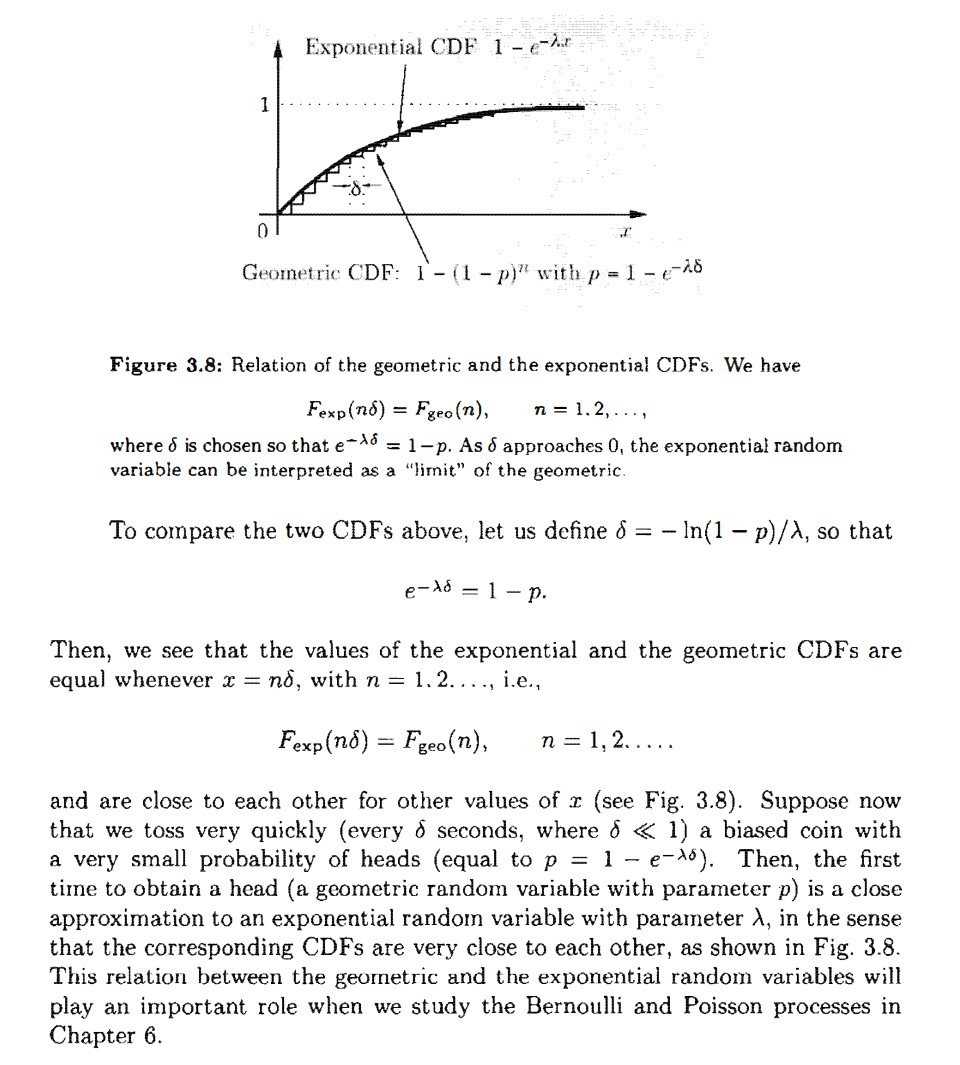

Geometric CDF

$$ F_{\text{geo}}(n) = \sum_{k = 1}^n p(1-p)^{k-1} = 1-(1-p)^n, \text{for } n = 1, 2, \dots $$Exponential CDF

$$ F_{\text{exp}}(x) = P(X\le x) = 0, \text{ for } x\le0,\\ F_{\text{exp}}(x) = \int_{0}^x \lambda e^{-\lambda t}\mathrm dt = 1 - e^{-\lambda x}, \text{for }x\ge 0. $$Exponential Distribution is Memoriless, like Geometric:

$$ P(X \ge c + x| X \ge c) = e^{-\lambda x} = P(X \ge x)\\ $$The relationship:

Normal Random Variables

$$ f_X(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}e^{-(x-\mu)^2/2\sigma^2}\\ E[X] =\mu\\ \text{var}(X) = \sigma^2 $$Gaussian is good, since adding two Gaussian functions resulting in a new Gaussian functions. And with a huge mount of samples, the distribution is close to Gaussian(Central limit theorem).

The Standard Normal Random Variable

Normal(Gaussian)

$$ Y = \frac{X - \mu}{\sigma}\\ f_Y(y) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{-y^2/2}\\ E[Y] = 0\\ \text{var}(Y) = 1\\ $$The CDF of Normal Random Variable $\Phi(y)$ can not be derived directly, we can use the standard normal table to get the value.

$$ \Phi(-y) = 1 - \Phi(y) $$Multiple Continuous Random Variables

Joint PDFs

The two continuous RVs X and Y, with the same experiment, are jointly continuous if they can be described by a joint PDF $f_{X, Y}$ , where $f_{X, Y}$ is a nonnegative function that satisfies

$$ P((X, Y) \in B) = \iint_{(x, y)\in B} f(X, Y)\mathrm d x\mathrm dy $$for every subset B of the two-dimensional plane. In particular, when B is the form $B = \{(x, y)|a\le x \le b, c\le y \le d\}$ , we have

$$ P(a\le X \le b, c \le Y \le d) = \int_c^d\int_a^bf_{X, Y}(x, y)\mathrm dx\mathrm dy $$Normalization

$$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty\int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{X, Y}(x, y)\mathrm dx\mathrm dy = 1 $$Interpretation(Small rectangle)

$$ P(a\le X \le a + \delta, c \le Y \le c + \delta) \approx f_{X, Y}(a, c)\cdot\delta^2 $$Marginal PDF

$$ P(X\in A) = P(X \in A, Y \in (-\infty, \infty)) = \int_A \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{X, Y}(x, y)\mathrm dy\mathrm dx $$ $$ f_X(x) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{X, Y}(x, y)\mathrm dy\\ f_Y(y) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{X, Y}(x, y)\mathrm dx $$Joint CDF

If X and Y are two RVs asscociated with the same experiment, then the joint CDF of X and Y is the function

$$ F_{X, Y}(x, y) = P(X\le x, Y\le y) = P(X\le x|Y\le y)P(Y\le y) = \int_{-\infty}^y\int_{-\infty}^x f_{X, Y}(u, v)\mathrm du\mathrm dv $$Conversely

$$ f_{X, Y}(x, y) = \frac{\partial^2F_{X, Y}}{\partial x\partial y}(x, y) $$Expectations

$$ E[g(X, Y)] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty\int_{-\infty}^\infty g(x, y)f_{X, Y}(x, y)\mathrm dx\mathrm dy $$If g is linear, of the form of $g(x, y) = ax + by + c$ , then

$$ E[g(X, Y)] = aE[X] + bE[Y] + c $$X and Y are called independent if

$$ f_{X, Y}(x, y) = f_X(x)f_Y(y) $$Conditional and Independence

Conditional PDFs

Let X and Y be continuous RVs with joint PDF $f_{X, Y}$ . For any $f_Y(y) \gt 0$ , the conditional PDF of X given Y = y is defined by

$$ f_{X|Y}(x|y) = \frac{f_{X, Y}(x, y)}{f_Y(y)} $$Discrete case:

$$ p_{X|Y}(x|y) = \frac{p_{X, Y}(x, y)}{p_Y(y)} $$By analogy, for fixed y would like:

$$ P(x \le X \le x + \delta|Y = y) \approx f_{X|Y}(x|y)\cdot\delta $$But {Y = y} is a zero-probability event.

Let $B = \{y\le Y \le y + \epsilon\}$ , for small $\epsilon > 0$ . Then

$$ P(x \le X \le x + \delta|Y \in B) \approx \frac{P(x \le X \le x + \delta)}{P(y \le Y \le y + \epsilon)} \approx \frac{f_{X, Y}(x, y)\cdot\epsilon\delta}{f_Y(y)\cdot\epsilon} \approx f_{X|Y}(x|y)\cdot\delta $$Limiting case when $\epsilon \rightarrow 0$ , to define conditional PDF where the denominator is a zero-probability event.

Conditional Expectation

The conditional expectation of X given that A has happened is defined by

$$ E[X|A] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty xf_{X|A}(x)\mathrm dx $$For a function g, we have

$$ E[g(X)|A] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty g(x)f_{X|A}(x)\mathrm dx $$Total expectation theorem

Le $A_1, A_2, \dots A_n$ be disjoint events that form a partition of the sample space $\Omega$ . And $P(A_i)\gt 0$ for all $i$ . Then

$$ E[g(X)] = \sum_{i=1}^n P(A_i)E[g(X)|A_i] $$Conditional Expectation

The conditional expectation of X given that $Y = y$ has happened is defined by

$$ E[X|Y=y] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty xf_{X|Y}(x|y)\mathrm dx $$For a function g, we have

$$ E[g(X)|Y=y] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty g(x)f_{X|Y}(x|y)\mathrm dx $$Total expectation theorem

$$ E[X] = E_{Y}\left[E_{X|Y}[X|Y]\right] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty E[X|Y = y]f_Y(y)\mathrm dy $$Independence

Two continuous RVs $X$ and $Y$ are independent if and only if

$$ f_{X, Y}(x, y) = f_X(x)f_Y(y) $$Independence is the same as the condition

$$ f_{X|Y}(x|y) = f_X(x) $$If $X$ and $Y$ are independent, then

$$ E[XY] = E[X]E[Y]\\ E[g(x)h(y)] = E[g(x)]E[h(y)], \forall g, h\\ \text{var}(X + Y) = \text{var}(X) + \text{var}(Y)\\ $$The continuous Bayes’s rule

$$ f_{Y|X}(y|x) = \frac{f_Y(y)f_{X|Y}(x|y)}{f_Y(y)} $$Based on the normalization property $\int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{X|Y}(x|y)\mathrm dx = 1$ ,

$$ f_{Y|X}(y|x) = \frac{f_Y(y)f_{X|Y}(x|y)}{\int_{-\infty}^\infty f_X(t)f_{Y|X}(y|t)\mathrm dt} $$Derived distributions and Entropy

Derived Distribution

If we want to calculate the expectation $E[g(X)]$ , there’s no need to calculate the PDF $f_X$ of $X$ .

But sometimes we want the PDF $f_Y$ of $Y = g(X)$ , where $Y$ is a new RV.

Principal Method

Two-step procedure for the calculation of the PDF of a function $Y=g(X)$ of a continuous RV $X$

- Calcualte the CDF $F_Y$ of $Y$ : $F_Y(y) = P(Y \le y)$

- Differentiate $F_Y$ to obtain the PDF $f_Y$ of $Y$ : $f_Y(y) = \frac{\mathrm d F_Y}{\mathrm d y}(y)$

The PDF of $Y=aX + b$

Suppose $a>0$ and $b$ are constants.

$$ f_Y(y) = \frac{\mathrm d F_Y}{\mathrm d y}(y) = \frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d y} F_X(\frac{y-b}{a}) = \frac{1}{a}f_X(\frac{y-b}{a}) $$If $X$ is Normal, then $Y = aX + b$ is also Normal.

Suppose X is normal with mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$ . Then

$$ f_Y(y) = \frac{1}{a\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}}\exp\left(-\frac{(y-b-a\mu)^2}{2a^2\sigma^2}\right) $$ $$ Y = aX + b \sim N(a\mu + b, a^2\sigma^2) $$The PDF of a strictly monotonic function

Suppose $g$ is a strictly monotonic function and that for some function $h$ and all $x$ in the range of $X$ we have

$$ y = g(x) \text{ if and only if } x = h(y) $$Assume that $h$ is differentiable.

Then the PDF of $Y = g(X)$ is given by

$$ f_Y(y) = \frac{\mathrm d F_Y}{\mathrm d y}(y) = \frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d y} F_X(h(y)) = f_X(h(y))\left|\frac{\mathrm d h}{\mathrm d y}(y)\right| $$Entropy

Defintion

Discrete case

Let $X$ be a discrete RV defined on probability space $(\Omega, \mathcal F, P)$ . The entropy of $X$ is defined by

$$ H(X) = -E[\ln p_X(X)] = -\sum_{k} p_X(x_k)\ln p_X(x_k) $$Continuous case

Let $X$ be a continuous RV defined on probability space $(\Omega, \mathcal F, P)$ . The differential entropy of $X$ is defined by

$$ H(X) = -E[\ln f_X(X)] = -\int_{-\infty}^\infty f_X(x)\ln f_X(x)\mathrm dx $$Remarks

- a special expectation of a random variable

- a measure of uncertainty in a random experiment

- the larger the entropy, the more uncertain the experiment

- For a deterministic event, the entropy is zero

- The base of logarithm can be different. Changing the base od the logarithm is equivalent to multiplying the entropy by a constant.

- With base 2, we say that the entropy is in units of bits

- With base e, we say that the entropy is in units of nats

- The basis of information theory

Maximum entropy distributions

• Maximum entropy distributions

− Distributions with maximum entropy under some constraints

− Gaussian, exponential, and uniform distributions are all maximum entropy distributions under certain conditions

• Why studying maximum entropy distributions?

− The most random distribution, reflecting the maximum uncertainty about the quantity of interest

Definition

Discrete Case

X can be a finite number of values $x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n$ , satisfying $p_X(x_k) = p_k.$

We have the following optimization problem:

$$ \max_{X} H(X) = \max_{p_1, p_2, \dots, p_n} \left(-\sum_{k=1}^n p_k\ln p_k\right)\\ \text{s.t.} \sum_{k=1}^n p_k = 1, p_k \ge 0 \text{ for } k = 1, 2, \dots, n $$Solution

Applying the Lagrange multiplier method, we have

$$ L(p_1, p_2, \dots, p_n;\lambda) = -\sum_{k=1}^n p_k\ln p_k + \lambda\left(\sum_{k=1}^n p_k - 1\right)\\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial p_k} = -\ln p_k - 1 + \lambda = 0\\ \Rightarrow p_k = e^{\lambda - 1}\\ $$Note that the above is true for all $k$ . So we have

$$ p_k = e^{\lambda - 1} = \frac1{n}\text{ for } k = 1, 2, \dots, n. $$Continuous Case 1

$X \in [-\infty, \infty]$ .Constrain on mean and variance,

we have the following optimization problem:

In detail,

$$ \max_{X} H(X) = \max_{\mu, \sigma^2} \left(-\int_{-\infty}^\infty f_X(x)\ln f_X(x)\mathrm dx\right)\\ \text{s.t. }\int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x)\mathrm dx = 1, \quad \int_{-\infty}^\infty xf(x)\mathrm dx = \mu, \quad \int_{-\infty}^\infty x^2f(x)\mathrm dx = \sigma^2 + \mu^2 $$Solving the above problem, we have Gaussian distribution with mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$ .

$$ f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}}\exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) $$Solution

For all measurable functions $g$ , we have

$$ G(t) = h(f + tg) = -\int_{\infty}^\infty (f(x) + tg(x))\ln (f(x) + tg(x))\mathrm dx $$Therefore,

$$ h(f_{opt})\ge h(f_{opt} + tg)\\ \Rightarrow G(0)\ge G(t), \forall t \in \R $$ $G(t)$ reaches its maximum at $t = 0$ .Then apply the Lagrange multiplier method, we have

$$ \overline{G}(t) = G(t) + c_0h_0(t) + c_1h_1(t) + c_2h_2(t)\\ $$Get the derivative of $\overline{G}(t)$ with regard to $t$ , and let the derivative equal to zero.

Continuous Case 2

$X \in [0, \infty)$ .Constrain on mean only, we have the following optimization problem:

$$ \max_{X}h(X), \\ \text{s.t. }E[X] = \mu $$In detail,

$$ \max_{X} H(X) = \max_{\mu} \left(-\int_{0}^\infty f_X(x)\ln f_X(x)\mathrm dx\right)\\ \text{s.t. }\int_{0}^\infty f(x)\mathrm dx = 1, \quad \int_{0}^\infty xf(x)\mathrm dx = \mu $$Solving the above problem, we have exponential distribution with parameter $\lambda$ .

$$ f(x) = \lambda e^{-\lambda x}, x \in [0, \infty) $$Continuous Case 3

$X \in [a, b]$ .No constrain, we have the unconstrained optimization problem:

$$ \max_{X}h(X) $$In detail,

$$ \max_{X} H(X) = \max_{a, b} \left(-\int_{a}^b f_X(x)\ln f_X(x)\mathrm dx\right)\\ \text{s.t. }\int_{a}^b f(x)\mathrm dx = 1 $$Solving the above problem, we have uniform distribution within $[a, b]$ .

$$ f(x) = \frac{1}{b-a}, x \in [a, b] $$Convolution, covariance, correlation, and conditional expectation

Convolution

Discrete case

$$ \begin{align*} p_W(w) &= P(X+Y=w)\\ &= \sum_{x}P(X=x, Y=w-x)\\ &= \sum_{x}P(X=x)P(Y=w-x)\\ &= \sum_{x}p_X(x)p_Y(w-x)\\ \end{align*} $$PMF $p_W$ is the convolution of PMFs $p_X$ and $p_Y$ .

The distribution of $X+Y$

Mechanics:

- Put the PMF’s on top of each other

- Flip the PMF of $Y$

- Shift the flipped PMF by $w$ (to the right if $w>0$ )

- Cross-multiply and add

Continuous Case

$$ \begin{align*} &W = X+Y, X, Y \text{ are independent}\\ &P(W\le w|X=x) = P(Y\le w-x)\\ &f_{W|X}(w|x) = f_Y(w-x)\\ &f_{W, X}(w, x) = f_X(x)f_Y(w-x)\\ &f_W(w) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_X(x)f_Y(w-x)\mathrm dx\\ \end{align*} $$Sum of 2 independent normal RVs

$$ \begin{align*} & X\sim N(\mu_1, \sigma_1^2), Y\sim N(\mu_2, \sigma_2^2)\\ &f_{X,Y}(x, y) = \frac{1}{2\pi \sigma_x\sigma_y}\text{exp}\left\lbrace-\frac{(x-\mu_x)^2}{2\sigma_x^2} - \frac{(y-\mu_y)^2}{2\sigma_y^2}\right\rbrace \end{align*} $$which is constant on the ellipse(circle if $\sigma_x = \sigma_y$ ).

$$ \begin{align*} X\sim N(0, \sigma_x), &Y\sim N(0, \sigma_y)\\ W &= X+Y\\ f_W(w) &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{X,Y}(x, w-x)\mathrm dx\\ &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{1}{2\pi \sigma_x\sigma_y}\text{exp}\left\lbrace-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma_x^2} - \frac{(w-x)^2}{2\sigma_y^2}\right\rbrace\mathrm dx\\ =ce^{-\gamma \omega^2} \end{align*} $$ $W$ is Normal.Mean = 0, Variance = $\sigma_x^2 + \sigma_y^2$

Same argument for nonzero mean case.

The difference of two independent RVs

$X$ and $Y$ are independent exponential RVs with parameter $\lambda$ .Fix some $z\ge 0$ and note that $f_Y(x-z)$ is non zero when $x\ge z$ .

$$ \begin{align*} Z &= X - Y\\ f_Z(z) &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_X(x)f_{-Y}(z - x)\mathrm dx\\ &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_X(x)f_{Y}(x - z)\mathrm dx\\ &= \int_{z}^\infty \lambda e^{-\lambda x}\lambda e^{-\lambda(x-z)}\mathrm dx\\ &= \frac{\lambda}{2}e^{-\lambda z} \end{align*} $$The answer for the case $z\le 0$

$$ f_{X-Y}(z) = f_{Y-X}(z) = f_Z(-z) $$The first quality holds by symmetry.

Covariance and Correlation

Definition

The covariance of two RVs $X$ and $Y$ , denoted by $\text{cov}(X, Y)$ , is defined by

$$ \text{cov}(X, Y) = E\left[(X - E[X])(Y - E[Y])\right] $$or,

$$ \text{cov}(X, Y) = E[XY] - E[X]E[Y] $$ $X$ and $Y$ are **uncorrelated** if $\text{cov}(X, Y) = 0$ .Zero mean case $\text{cov}(X, Y) = E[XY]$

Properties

$$ \text{cov}(X, Y) = \text{var}(X, Y)\\ \text{cov}(X, aY+b) = a\cdot\text{cov}(X, Y)\\ \text{cov}(X, Y+Z) = \text{cov}(X, Y) + \text{cov}(X, Z)\\ \text{independent} \Rightarrow \text{cov}(X, Y) = 0(\text{converse is not true}) $$Variance of the sum of RVs

$$ \text{var}\left(\sum_{i = 1}^nX_i\right) = \sum_{i = 1}^n\text{var}(X_i) + \sum_{\lbrace(i, j)|i\ne j\rbrace}\text{cov}(X_i, X_j) $$In particular,

$$ \text{var}(X_1 + X_2) = \text{var}(X_1) + \text{var}(X_2) + 2\text{cov}(X_1, X_2) $$Correlation coefficient

The correlation coefficient $\rho(X, Y)$ of two RVs $X$ and $Y$ that have nonzero variance is defined as

$$ \begin{align*} \rho &= E\left[\frac{(X - E[X])}{\sigma_X} \cdot \frac{(Y - E[Y])}{\sigma_Y}\right]\\ &= \frac{\text{cov}(X, Y)}{\sigma_X\sigma_Y} \end{align*} $$- $-1 \le \rho \le 1$

- $|\rho| = 1 \Leftrightarrow (X-E[X]) = c(Y-E[Y])$

- Independent $\Rightarrow \rho = 0(\text{converse is not true})$

Conditional expected value

$$ E[X|Y = y] = \sum_x xp_{X|Y}(x|y) $$Conditional expectation

Definition

$$ E[X|Y = y] = \begin{cases} \sum_x xp_{X|Y}(x|y), & X \text{discrete},\\ \int_{-\infty}^\infty xf_{X|Y}(x|y)\mathrm dx, & X \text{continuous}. \end{cases} $$ $E[X|Y=y]$ is a function of $y$ . $$ E[X|Y = y] = \frac{y}{2}(\text{number})\\ E[X|Y] = \frac{Y}{2}(\text{RV}) $$Law of iterated expectations

$$ E[X] = E[E[X|Y]] = \begin{cases} \sum_y E[X | Y = y]p_Y(y), & Y \text{discrete},\\ \int_{-\infty}^\infty E[X|Y = y]f_Y(y)\mathrm dy, & Y \text{continuous}. \end{cases} $$Conditional expectation as an estimator

Denote the conditional expectation

$$ \hat{X} = E[X|Y] $$as an estimator of $X$ given $Y$ , and the estimation error

$$ \tilde{X} = X - \hat{X} $$is a RV.

Properties of the estimator:

Unbiased

For any possible $Y=y$ :

$$ E[\tilde{X}|Y] = E[X - \hat{X} | Y] = E[X | Y] - E[\hat{X}|Y] = \hat{X} - \hat{X} = 0 $$By the law of iterated expectations

$$ E[\tilde{X}] = E[E[\tilde{X}|Y]] = 0 $$Uncorrelated

$$ E[\hat{X}\tilde{X}] = E[E[\hat{X}\tilde{X}|Y]] = E[\hat{X}E[\tilde{X}|Y]] = 0 $$ $$ \text{cov}(\hat{X}, \tilde{X}) = E[\hat{X}\tilde{X}] - E[\hat{X}]E[\tilde{X}] = 0 $$Since $X = \hat{X} + \tilde{X}$ , the variance of X can be decomposed as

$$ \text{var}(X) = \text{var}(\hat{X}) + \text{var}(\tilde{X}) $$ $$ \text{var}(\tilde{X}) = \text{var}(E[X|Y]) $$Conditional variance

$$ \text{var}(X|Y) = E[(X - E[X|Y])^2|Y] = E[\tilde{X}^2|Y] $$here comes the law of total variance:

$$ \text{var}(X) = \text{var}(E[X|Y]) + E[\text{var}(X|Y)] $$The total variability is avarage variability within sections + variability between sections.

Law of iterated expectations

$$ E[X] = E[E[X|Y]] = \sum_y E[X|Y = y]p_Y(y) $$Conditional variance

$$ \text{var}(X|Y) = E[(X - E[X|Y])^2|Y] = E[\tilde{X}^2|Y] $$Law of total variance

$$ \text{var}(X) = \text{var}(E[X|Y]) + E[\text{var}(X|Y)] $$Transforms and sum of a random number of random variables

The transform associated with a RV $X$ is a function $M_X(s)$ of a scalar parameter $s$ , defined by

$$ M_X(s) = E[e^{sX}] = \begin{cases} \sum_x e^{sx}p_X(x), & X \text{discrete},\\ \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{sx}f_X(x)\mathrm dx, & X \text{continuous}. \end{cases} $$Remarks

- a function of $s$ , rather than a number

- not necessarily defined for all (complex) s

- always well defined for $\Re(s)=0$

- compared with Laplace transform

Properties

Sanity Checks

$$ M_X(0) = 1\\ |M_X(s)| \le 1 \text{ for } \Re(s) = 0 $$Linear operation

$$ M_{aX + b}(s) = e^{bs}M_X(as)\\ M_{X + Y}(s) = M_X(s)M_Y(s) (\text{if X, Y independent}) $$Expected Values

$$ E[X^n] = \frac{\partial^n M_X(s)}{\partial s^n}\bigg|_{s=0} $$ $$ P(X = c) = \lim_{N\rightarrow \infty}\frac 1N\sum_{k = 1}^N M_X(jk)e^{-jkc} $$since

$$ \lim_{N\rightarrow \infty}\frac 1N\sum_{k = 1}^N M_X(jk)e^{-jkc} = \sum_{x = 1}^\infty p_X(x)\lim_{N\rightarrow \infty}\frac 1N\sum_{k = 1}^N e^{-jc(k - x)} = \sum_{x = 1}^\infty p_X(x)\lim_{N\rightarrow \infty}\frac{1}{N} \frac{e^{j(x-c)} - e^{Nj(x - c)}}{1-e^{j(x-c)}} = p_X(c) $$Example

$X$ is a Poisson RV with parameter $\lambda$ $$ p_X(x) = \frac{\lambda^x}{x!}e^{-\lambda} $$ $$ M(s) = \sum_{x = 0}^\infty e^{sx}\frac{\lambda^x}{x!}e^{-\lambda} = e^{-\lambda}\sum_{x = 0}^\infty \frac{(e^s\lambda)^x}{x!} = e^{-\lambda}e^{e^s\lambda} = e^{\lambda(e^s - 1)} $$ $X$ is an exponential RV with parameter $\lambda$ $$ f_X(x) = \lambda e^{-\lambda x} $$ $$ M(s) = \int_0^\infty e^{sx}\lambda e^{-\lambda x}\mathrm dx = \frac{\lambda}{\lambda - s} $$ $Y$ is a standard normal RV, $$ M_Y(s) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{-(y^2/2)}e^{sy}\mathrm dy = e^{s^2/2} $$Consider $X = \sigma Y + \mu$

$$ M_X(s) = e^{s^2\sigma^2/2 + \mu s} $$Inversion of transforms

Inversion Property

The transform $M_X(s)$ associated with a RV $X$ uniquely determines the CDF of $X$ , assuming that $M_X(s)$ is finite for all $s$ in some interval $[-a, a]$ , where $a$ is a positive number.

Example:

$$ \begin{align*} M(s) &= \frac{pe^s}{1 - (1 - p)e^s}\\ &= pe^s(1 + (1-p)e^s + (1-p)^2e^{2s} + \dotsb)\\ &= \sum_{k = 1}^\infty p(1-p)^{k - 1}e^{ks} \end{align*} $$The probability $P(X = k)$ is found by reading the coefficient of the term $e^{ks}$ :

$$ P(X = k) = p(1-p)^{k-1} $$Transform of Mixture of Distributions

Let $X_1,\dotsb, X_n$ be continuous RVs with PDFs $f_{X_1}, \dotsb, f_{X_n}$ .

The value $y$ of RV $Y$ is generated as follows: an index $i$ is chosen with a corresponding probability $p_i$ , and $y$ is taken to be equal to the value $X_i$ . Then,

$$ f_Y(y) = p_1f_{X_1}(y) + \dotsb + p_nf_{X_n}(y)\\ M_Y(s) = p_1M_{X_1}(s) + \dotsb + p_nM_{X_n}(s) $$Sum of independend RVs

Let $X$ and $Y$ be independent RVs, and let $Z = X + Y$ . The transform associated with $Z$ is

$$ M_Z(s) = M_X(s)M_Y(s) $$Since

$$ M_Z(s) = E[e^{sZ}] = E[e^{s(X + Y)}] = E[e^{sX}e^{sY}] = E[e^{sX}]E[e^{sY}] = M_X(s)M_Y(s) $$Generalization:

A collection of independent RVs: $X_1, \dotsb, X_n$ , $Z = X_1 + \dotsb + X_n$ ,

$$ M_Z(s) = M_{X_1}(s)\dotsb M_{X_n}(s) $$Example

Let $X_1, \dotsb, X_n$ be independent Bernoulli RVs with a common parameter $p$ :

$$ M_{X_i}(s) = 1 - p + pe^s $$ $Z = X_1 + \dotsb + X_n$ is binomial with parameters n and p: $$ M_z(s) = (1 - p + pe^s)^n $$Let $X$ and $Y$ be independent Poisson RVs with means $\lambda$ and $\mu$ , and let $Z = X + Y$ . Then $Z$ is still Poisson with mean $\lambda + \mu$ .

$$ M_Z(s) = M_X(s)M_Y(s) = e^{(\lambda +\mu)(e^s - 1)} $$Let $X$ and $Y$ be independent Gaussian RVs with means $\mu_x$ and $\mu_y$ , and variances $\sigma_x^2, \sigma_y^2$ . And let $Z = X + Y$ . Then $Z$ is still Gaussian with mean $\mu_x + \mu_y$ and variance $\sigma_x^2 + \sigma_y^2$

$$ M_X(s) = \exp\bigg\lbrace\frac{\sigma_x^2s^2}{2} + \mu_x s\bigg\rbrace\\ M_Y(s) = \exp\bigg\lbrace\frac{\sigma_y^2s^2}{2} + \mu_y s\bigg\rbrace\\ M_Z(s) = M_X(s)M_Y(s) = \exp\bigg\lbrace\frac{(\sigma_x^2 + \sigma_y^2)s^2}{2} + (\mu_x + \mu_y)s\bigg\rbrace $$Consider

$$ Y = X_1 + \dotsb + X_N $$where $N$ is a RV that takes integer values, and $X_1, \dotsb, X_N$ are identically distributed RVs.

Assume that $N, X_1, \dotsb$ are independent.

$$ E[Y|N = n] = E[X_1 + X_2 + \dotsb + X_n|N = n] = nE[X]\\ E[Y|N] = NE[X]\\ E[Y] = E[E[Y|N]] = E[NE[X]] = E[N]E[X] $$For the variance,

$$ E[Y|N] = NE[X]\\ \text{var}(E[Y|N]) = (E[X])^2\text{var}(N)\\ \text{var}(Y|N=n) = n\text{var}(X)\\ \text{var}(Y|N) = N \text{var}(X)\\ E[\text{var}(Y|N)] = E[N]\text{var}(X)\\ $$So,

$$ \text{var}(Y) = E[\text{var}(Y|N)] + \text{var}(E[Y|N]) = E[N]\text{var}(X) + (E[X])^2\text{var}(N) $$For transform,

$$ E[e^{sY}|N = n] = E[e^{sX_1}\dotsb e^{sX_n}|N = n] = E[e^{sX}]^n = (M_X(s))^n\\ M_Y(s) = E[e^{sY}] = E[E[e^{sY}|N]] = E[(M_X(s))^N] = \sum_{n = 0}^\infty (M_X(s))^n p_N(n) = \sum_{n = 0}^\infty e^{n\log M_X(s)}p_N(n) = M_N(\log M_X(s)) $$Summary on Properties

Consider the sum

$$ Y = X_1 + \dotsb + X_N $$where $N$ is a RV that takes integer values, and $X_1, X_2, \dotsb$ are identically distributed RVs. Assume that $N$ , $X_1, X_2, \dotsb$ are independent.

$$ E[Y] = E[N]E[X]\\ \text{var}(Y) = E[N]\text{var}(X) + (E[X])^2\text{var}(N)\\ M_Y(s) = M_N(\log M_X(s)) $$Example

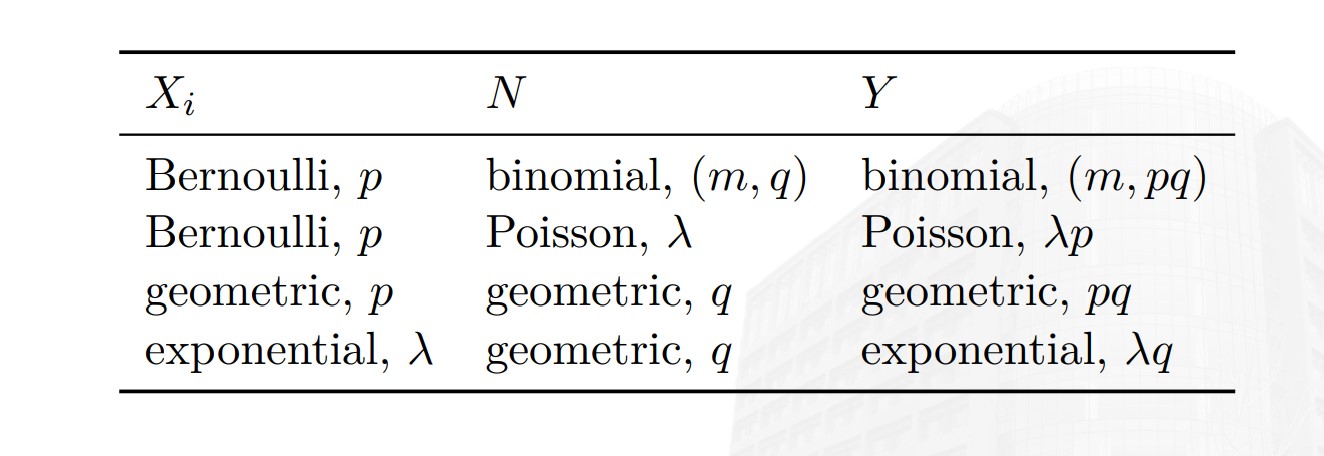

Assume that $N$ and $X_i$ are both geometrically distributed with parameters $p$ and $q$ respectively. All of these RVs are independent. $Y = X_1 + \dotsb + X_N$

$$ M_N(s) = \frac{pe^s}{1 - (1-p)e^s}\\ M_X(s) = \frac{qe^s}{1 - (1-q)e^s}\\ M_Y(s) = M_N(\log M_X(s)) = \frac{pqe^s}{1 - (1-pq)e^s} $$ $Y$ is also geometrically distributed, with parameter $pq$ .Weak law of large numbers

Markov inequality

If a RV $X$ can only take nonnegative values, then

$$ P(X \ge a) \le \frac{E[X]}{a}, \text{ for all } a \gt 0. $$Intuition: If a nonnegative RV has a small mean, then the probability that it takes a large value must be small。

Fix a positive number $a$ ,

$$ E[X] = \int_0^\infty xf_X(x)dx = \int_0^a xf_X(x)dx + \int_a^\infty xf_X(x)dx \ge 0 + \int_a^\infty xf(x)dx \ge \int_a^\infty af_X(x)dx = aP(X \ge a) $$Chebyshev’s Inequality

If $X$ is a RV with mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$ , then

$$ P(|X - \mu| \ge c) \le \frac{\sigma^2}{c^2} $$Intuition: If a RV has small variance, then the probability that it takes a value far from its mean is also small.

$$ \begin{align*} \sigma^2 &= \int (x - \mu)^2f_X(x)\mathrm dx\\ &\ge \int_{-\infty}^{\mu - c} (x - \mu)^2f_X(x)\mathrm dx + \int_{ \mu + c}^\infty (x - \mu)^2f_X(x)\mathrm dx\\ &\ge \int_{-\infty}^{\mu - c} c^2f_X(x)\mathrm dx + \int_{ \mu + c}^\infty c^2f_X(x)\mathrm dx\\ &= \int_{|x - \mu| \ge c} c^2f_X(x)\mathrm dx\\ &=c^2P(|X - \mu| \ge c) \end{align*} $$The upperbounds of $\sigma^2$ :

$$ X \in [a, b]\\ \sigma^2 \le (b - a)^2/4 $$Chernoff inequality

If a RV $X$ has MGF $M_X(s)$ , then

$$ P(X \ge a) \le e^{-\max_{s\ge 0}\left(sa - \ln M_X(s)\right)} $$or, for $s \ge 0$

$$ P(X\ge a) \le e^{-sa}M_X(s) $$for $s \lt 0$

$$ P(X \le a) \le e^{-sa}M_X(s) $$proof: for $s \ge 0$

$$ M_X(s) = \int_{-\infty}^a e^{sx}f_X(x)\mathrm dx + \int_a^{\infty} e^{sx}f_X(x)\mathrm dx\\ \ge 0 + e^{sa}\int_a^{\infty} f_X(x)\mathrm dx = e^{sa}P(X \ge a) $$Weak law of large numbers

Let $X_1, X_2, \dots$ be independent identically distributed (i.i.d.) RVs with finite mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$

$$ M_n = \frac{X_1 + X_2 + \dotsb + X_n}{n}\\ E[M_n] = \mu\\ \text{var}(M_n) = \frac{\sigma^2}{n} $$Applying the Chebyshev inequality and we get:

$$ P(|M_n - \mu| \ge \epsilon) \le \frac{\text{var}(M_n)}{\epsilon^2} = \frac{\sigma^2}{n\epsilon^2} $$For large $n$ , the bulk of the distribution of $M_n$ is concentrated near $\mu$

Theorem

Let $X_1, X_2, \dots$ be independent identically distributed (i.i.d.) RVs with finite mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$ . For every $\epsilon \gt 0$ , we have

$$ P(|M_n - \mu| \ge \epsilon) = P\left(\left|\frac{X_1 + \dotsb + X_n}{n} - \mu\right|\ge \epsilon\right) \rightarrow 0, \text{ as } n \rightarrow \infty $$ $M_n$ converges **in probability** to $\mu$ .Convergence “in Probability”

Theorem: Convergence in Probability

Let $\lbrace Y_n\rbrace$ (or $Y_1, Y_2, \dots$ ) be a sequence of RVs(not necessarily independent), and let $a$ be a real number. We say that the sequence $Y_n$ converges to $a$ in probability, if for every $\epsilon \gt 0$ , we have

$$ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} P(|Y_n - a| \ge \epsilon) = 0 $$(almost all) of the PMF/PDF of $Y_n$ , eventually gets concentrated (arbitrarily) close to $a$ .

Many types of convergence

Deterministic limits: $\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} a_n = a$

$$ |a_n - a|\le \epsilon, \forall n \ge N, \epsilon \gt 0 $$Convergence in probability: $X_n\stackrel P{\rightarrow} X$

$$ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty}P(|X_n - X|\ge \epsilon) = 0, \forall \epsilon \gt 0 $$(WLLN)

Convergence in Distribution: $X_n \stackrel{D}{\rightarrow} X$

$$ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} P(X_n \le x) = P(X \le x), \forall x $$For all points of $x$ at which the function $F_X(x) = P(X\le x)$ is continuous.

(CLT)

Convergence with probability $1$ (almost surely): $X_n \stackrel{\text{a.s.}}{\rightarrow} X$

$$ P\left(\lbrace\omega\in \Omega: \lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}X_n(\omega) =X(\omega)\rbrace\right) = 1 $$or

$$ P\left(\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}X_n(\omega) =X(\omega)\right) = 1 $$Lemma:

$$ X_n \stackrel{\text{a.s.}}{\rightarrow} X \Leftrightarrow \lim_{m \rightarrow\infty}P(|X_n - X|\le \epsilon, \forall n \gt m) = 1, \forall \epsilon \gt 0\\ \Leftrightarrow P(|X_n - X|\gt \epsilon, \text{i.o.}) = 0, \forall \epsilon \gt 0 $$i.o. stand for infinitely often

(SLLN)

Convergence in Mean/in Norm: $X_n \stackrel{r}{\rightarrow}X$

if $E[X_n^r] \lt \infty$ for all $n$ and

$$ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty}E[|X_n - X|^r] = 0 $$Relations:

$$ \left(X_n\stackrel {\text{a.s.}}{\rightarrow} X\right) \Rightarrow\left(X_n\stackrel P{\rightarrow} X\right) \Rightarrow \left(X_n\stackrel D{\rightarrow} X\right) \\ \left(X_n\stackrel {r}{\rightarrow} X\right) \Rightarrow\left(X_n\stackrel P{\rightarrow} X\right) \Rightarrow \left(X_n\stackrel D{\rightarrow} X\right) \\ \forall r\ge s\ge 1, \left(X_n\stackrel {r}{\rightarrow} X\right) \Rightarrow\left(X_n\stackrel s{\rightarrow} X\right) $$The converse assertions fail in general!

The relation between “almost surely” and “in r-th mean” is complicated. There exist sequences which converge almost surely but

not in mean, and which converge in mean but not almost surely!

Central Limit Theorem

Theorem

Let $X_1, X_2, \dots$ be i.i.d. RVs with mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$ . Let

$$ Z_n = \frac{X_1 + X_2 + \dotsb + X_n - n\mu}{\sigma\sqrt{n}} $$Then

$$ \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty}P(Z_n\le z) = \Phi (z) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\int_{-\infty}^z e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}}\mathrm dx $$CDF of $Z_n$ converges to normal CDF(converge in distribution)

Normal Approximation Based on the Central Limit Theorem

Let $S_n = X_1 + \dotsb + X_n$ , where $X_i$ are $\text{i.i.d.}$ RVs with mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$ . If $n$ is large, the probability $P(S_n ≤ c)$ can be approximated by

treating $S_n$ as if it were normal, according to the following procedure.

- Calculate the mean $n\mu$ and the variance $n\sigma^2$ of $S_n$

- Calculate the normalinzd value $z = (c - n\mu)/(\sigma\sqrt{n})$

- Use the approxmation

where $\Phi(z)$ is available from the standard normal CDF.

Proof

Suppose that $X_1, X_2, \dots$ has mean zero.

$$ \begin{align*} M_{Z_n}(s) &= E[e^{sZ_n}]\\ &=E\left[\exp\left(\frac{s}{\sigma\sqrt{n}}\sum_{i = 1}^n X_i\right)\right]\\ &=\prod_{i = 1}^n E[e^{\frac{s}{\sigma\sqrt{n}}X_i}]\\ &=\prod_{i = 1}^n M_{X_i}\left(\frac{s}{\sigma\sqrt{n}}\right)\\ &=\left(M_{X}\left(\frac{s}{\sigma\sqrt{n}}\right)\right)^n\\ \end{align*} $$Suppose that the transform $M_X(s)$ has a second order Taylor series expansion around $s=0$ ,

$$ M_X(s) = a + bs + cs^2 + o(s^2) $$where $a = M_X(0) = 1, b = M_X'(0) = E[X] = 0, c = \frac{1}{2}M_X''(0) = \frac{\sigma^2}{2}$

Then

$$ M_{Z_n}(s) = \left(1 + \frac{s^2}{2n} + o\left(\frac{s^2}{n}\right)\right)^n $$As $n\rightarrow \infty$ ,

$$ \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty}M_{Z_n}(s) = \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty}\left(1 + \frac{s^2}{2n} + o\left(\frac{s^2}{n}\right)\right)^n = e^{\frac{s^2}{2}} $$Approxmation on binomial:

(De Moivre-Laplace Approxmation to the Binomial)

$$ P(k \le S_n \le l) = P\left(\frac{k - np}{\sqrt{np(1-p)}} \le \frac{S_n - np}{\sqrt{np(1 - p)}} \le \frac{l - np}{\sqrt{np(1 - p)}}\right)\\ \approx \Phi\left(\frac{l - np}{\sqrt{np(1 - p)}}\right) - \Phi\left(\frac{k - np}{\sqrt{np(1 - p)}}\right) $$The Strong Law of Large Numbers

Theorem

Let $X_1, X_2, \dots$ be i.i.d. RVs with mean $\mu$ .

$$ P(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}\frac{X_1 + \dots + X_n}{n} = \mu) = 1. $$Borel-Cantelli lemma & Bernoulli Process

Limit of set sequence

$$ \limsup_n A_n = \bigcap_{n = 1}^\infty \bigcup_{k = n}^\infty A_k\\ \liminf_n A_n = \bigcup_{n = 1}^\infty \bigcap_{k = n}^\infty A_k $$If upper limit equals to lower limit, the limit of set sequence exists.

$$ \limsup_n A_n \supseteq \liminf_n A_n\\ \limsup_n A_n = \liminf_n A_n = \lim_n A_n $$Upper limit can also be denoted as

$$ \limsup_n A_n = \{\omega: \omega \in A_n, \text{i.o.}\} = \lbrace A_n, \text{i.o.}\rbrace $$Borel-Cantelli Lemma

Let $\lbrace A_n, n = 1, 2, \dotsb\rbrace$ be a sequence of events, then

$$ \sum_{n = 1}^\infty P(A_n)\lt \infty \xRightarrow{} P(A_n, \text{i.o.}) = 0 $$Let $\lbrace A_n, n = 1, 2, \dotsb\rbrace$ be a sequence of independent events, then

$$ \sum_{n = 1}^\infty P(A_n) = \infty \xRightarrow{} P(A_n, \text{i.o.}) = 1 $$Stochastic process

A stochastic process is a mathematical model of a probabilistic experiment that evolves in time and generates a sequence of

numerical values.

- Bernoulli process(memoryless, discrete time)

- Poisson process(memoryless, continuous time)

The Bernoulli Process

is a sequence of independent Bernoulli trials, each with probability of success $p$ .

$$ P(\text{success}) = P(X_i = 1) = p\\ P(\text{failure}) = P(X_i = 0) = 1 - p $$Independence property: For any given time $n$ , the sequence of $X_{n + 1}, X_{n + 2}, \dots$ is also a Bernoulli process, and is independent from $X_1, \dots, X_n$

Memoryless property: Let $n$ be a given time and let $\overline T$ be the time of the first success after

time $n$ . Then $\overline T − n$ has a geometric distribution with parameter $p$ ,

and is independent of the RVs $X_1, \dots , X_n$ .

Interarrival times

Denote the $k$ th success as $Y_k$ , the $k$ th interarrival time as $T_k$ .

$$ T_1 = Y_1, T_k = Y_k - Y_{k - 1}, k = 2, 3, \dots $$represents the number of trials following the $(k - 1)$ th success until the next success.

Note that

$$ Y_k = T_1 + T_2 + \dotsb + T_k $$Alternative description of the Bernoulli process:

- Start with a sequence of independent geometric RVs $T_1, T_2, \dots$ with common parameter p, and let these stand for the interarrival times.

- Record a success at times $T_1$ , $T_1 + T_2$ , etc.

Splitting of a Bernoulli process

Whenever there is an arrival, we choose to either keep it (with probability $q$ ), or to discard it (with probability $1 − q$ ).

Both the process of arrivals that are kept and the process of discarded arrivals are Bernoulli processes, with success probability $pq$ and $p(1 − q)$ , respectively, at each time.

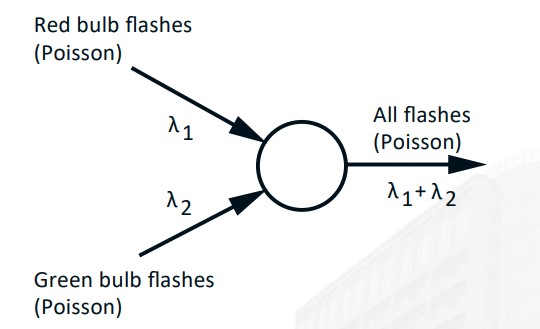

Merging of a Bernoulli process

In a reverse situation, we start with two independent Bernoulli processes (with parameters $p$ and $q$ respectively). An arrival is

recorded in the merged process if and only if there is an arrival in at least one of the two original processes.

The merged process is Bernoulli, with success probability $p+q−pq$ at each time step.

The Poisson Process

Definition

An arrival process is called a Poisson process with rate $λ$ if it has the following properties:

Time homogenity

$$ P(k, \tau) = P(k \text{ arrivals in interval of duration }\tau) $$Independence

Numbers of arrivals in disjoint time intervals are independent.

Small interval probabilities

$$ \begin{cases} 1 - \lambda\tau + o(\tau), & \text{if } k = 0,\\ \lambda\tau + o_1(\tau), & \text{if } k = 1,\\ o_k(\tau), & \text{if } k > 1. \end{cases} $$Bernoulli/Poisson Relation

In a short time interval $\delta$

$$ n = t / \delta\\ p = \lambda\delta\\ np = \lambda t $$For binomial PMF $p_S(k;n,p)$ ,

$$ \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty}p_S(k;n, p) = \lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}\frac{n!}{(n - k)!k!}p^k(1 - p)^{n - k} = \frac{(\lambda t)^k}{k!}e^{-\lambda t} = P(k, t) $$PMF of Number of Arrivals $N$

$$ P(k, \tau) = \frac{(\lambda\tau)^ke^{-\lambda\tau}}{k!} $$ $$ E[N_t] = \lambda t\\ \text{var}(N_t) = \lambda t $$Time $T$ of the first arrival

$$ F_T(t) = P(T \le t) = 1 - P(T \gt t) = 1 - e^{-\lambda t}, t\ge 0\\ f_T(t) = \lambda e^{-\lambda t}, t\ge 0 $$Memoryless property The time to next arrival is independent of the past.

Interarrival times

We also denote the time of the kth success as $Y_k$ , and denote the

kth interarrival time as $T_k$ . That is,

Note that

$$ Y_k = T_1 + T_2 + \dotsb + T_k $$ $$ f_{Y_k}(y) = \frac{\lambda^ky^{k-1}e^{-\lambda y}}{(k - 1)!}, y\ge 0 $$Merging Poisson Processes